This is the first article in a -part series exploring how C, C++, and Rust manage memory at a low level. We begin where the hardware does: with bytes. From there, we build up to objects, storage duration, lifetime, and aliasing, the vocabulary required to understand ownership.

You can discuss this article on Lobsters, Reddit (r/rust and r/programming) and Hacker News

Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Memory Is Just Bytes

A 64-bit processor sees memory as a flat array of addressable bytes. It does not know what a struct is. It does not know what an int is. When we execute mov rax, [rbx], the CPU fetches 8 bytes starting at the address in rbx, shoves them into rax, and moves on. The semantic meaning of those bytes, whether they represent a pointer, a floating-point number, or part of a UTF-8 string, exists only in our source code and the instructions we generate.

The machinery we build atop this substrate, effective types in C, object lifetime in C++, validity invariants in Rust, exists to help compilers reason about what the hardware cannot see. These abstractions enable optimization: if the compiler knows two pointers cannot alias, it keeps values in registers instead of reloading from memory. If it knows a reference is never null, it elides null checks. If it knows an object’s lifetime has ended, it reuses the storage.

Virtual Address Space

Modern operating systems do not give processes direct access to physical RAM. Instead, each process operates within its own virtual address space, a fiction maintained by the MMU (Memory Management Unit) that maps virtual addresses to physical frames. The C standard captures this abstraction explicitly: pointers in C reference virtual memory, and the language makes no guarantees about physical layout.

This abstraction buys us two properties. First, isolation: a pointer in process A cannot reference memory in process B. Dereferencing an unmapped address triggers a page fault, typically terminating the process. This is crucial for process-level security, since a compromised or buggy process cannot read credentials from our browser or corrupt our kernel’s data structures. Second, portability: code does not need to know the physical memory topology of the machine it runs on.

From our perspective, virtual memory means that the addresses we work with are translated by hardware before reaching DRAM. This translation has performance implications. TLB misses are expensive, but the abstraction holds: we operate on a contiguous address space that the OS manages for us.

Alignment

Not all byte addresses are equal. On x86-64, loading a On x86-64, misaligned access to a uint64_t from an address that is not divisible by 8 incurs a penalty. On stricter architectures like ARM (without unaligned access support) or older SPARC, it causes a hardware trap.uint64_t is handled transparently by the CPU with negligible overhead for most workloads. Intel has optimized this path since Sandy Bridge (2011). The penalty becomes significant only when a load straddles a cache line boundary (64 bytes) or, worse, a page boundary. On stricter architectures like ARM (without unaligned access support) or older SPARC, it causes a hardware trap.

The reason is mechanical. DRAM is accessed in aligned chunks. When the CPU requests data at address 0x1003, but the memory bus fetches 8-byte-aligned blocks, the memory controller must fetch two blocks (0x1000-0x1007 and 0x1008-0x100F), extract the relevant bytes, and reassemble them. This costs cycles.

The C standard formalizes this through the concept of alignment:

#include <stdalign.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

printf("alignof(int) = %zu\n", alignof(int)); // typically 4

printf("alignof(double) = %zu\n", alignof(double)); // typically 8

printf("alignof(max_align_t) = %zu\n", alignof(max_align_t)); // typically 16

}The alignof operator (C11/C23) returns the required alignment for a type. Accessing an object at an address that violates its alignment is undefined behavior,not because the standard is being pedantic, but because the hardware cannot reliably execute it. This allows the compiler to assume aligned access and emit instructions that would

trap or produce wrong results on misaligned addresses. On x86-64, misaligned scalar loads work but may cross cache lines; on stricter architectures like ARM, they trap.

Consider this concrete failure case from Modern C:

union {

unsigned char bytes[32];

complex double val[2];

} overlay;

// complex double typically requires 16-byte alignment (sizeof is 16)

complex double *p = (complex double *)&overlay.bytes[4]; // misaligned

*p = 1.0 + 2.0*I; // undefined behaviorOn x86-64 with alignment checking enabled, or on ARM, this crashes with a bus error. The pointer arithmetic is legal C, but the resulting address violates the alignment requirement of complex double. The hardware refuses.

Cache Lines and Memory Bandwidth

Alignment interacts with another hardware reality: cache lines. On modern x86-64 processors, the L1 cache operates on 64-byte lines. When we read a single byte, the CPU actually fetches 64 bytes. If our data structures are laid out poorly, we waste bandwidth fetching bytes we never use.

Worse, if a single logical datum spans two cache lines, every access requires two cache fetches. For a struct that straddles a 64-byte boundary, this doubles memory traffic.

This is why compilers insert padding between struct fields. Consider:

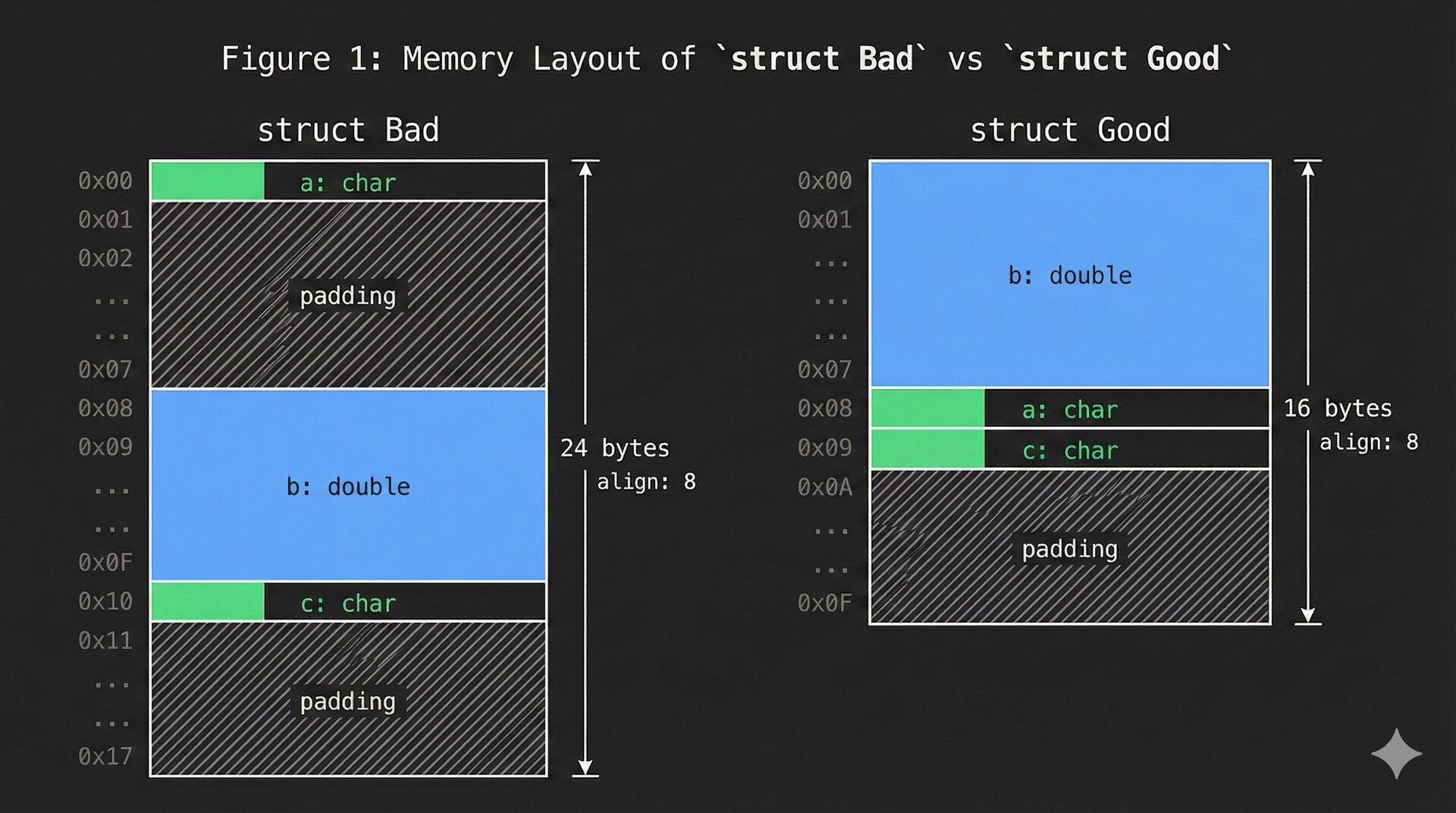

struct Bad {

char a; // 1 byte

// 7 bytes padding

double b; // 8 bytes

char c; // 1 byte

// 7 bytes padding (to align the whole struct)

};

struct Good {

double b; // 8 bytes

char a; // 1 byte

char c; // 1 byte

// 6 bytes padding

};sizeof(struct Bad) is 24 bytes. sizeof(struct Good) is 16 bytes. The compiler cannot reorder fields in C (the standard guarantees fields appear in declaration order with increasing addresses), so we must consider layout ourselves.

Yes, it's made with Gemini. I'm not good with Figma.

The Allocator’s View

When we call malloc(n), we do not receive exactly n bytes of usable memory. The allocator maintains metadata like chunk headers, size fields, and free-list pointers that live adjacent to our allocation. In glibc’s ptmalloc2, an allocated chunk looks roughly like this:

+------------------+

| prev_size | (8 bytes, used only if previous chunk is free)

+------------------+

| size |N|M|P| (8 bytes, includes flags in low 3 bits)

+------------------+

| user data... | <- pointer returned by malloc

| |

+------------------+The size field stores the chunk size with three flag bits: P (previous chunk in use), M (chunk obtained via mmap), and A (non-main arena). The actual usable size is size & ~0x7.

This has several implications. Every allocation has overhead, and small allocations suffer proportionally more: a 16-byte allocation requires at least 32 bytes of actual memory (16 bytes data + 16 bytes metadata, depending on the allocator). The allocator also imposes its own alignment; malloc guarantees alignment suitable for any primitive type (max_align_t), which is 16 bytes on most 64-bit platforms. Finally, memory is not truly free after free(). The allocator tracks allocated regions, and free() does not necessarily return memory to the OS. It typically returns it to a free list for reuse.

When we discuss ownership and resource management in later sections, keep this in mind: deallocating memory at the language level means returning bytes to the allocator. The allocator decides when (if ever) to return pages to the operating system.

Objects Are Bytes

The C standard makes this explicit: every object can be viewed as an array of unsigned char:

int x = 42;

unsigned char *bytes = (unsigned char *)&x;

for (size_t i = 0; i < sizeof(int); i++) {

printf("%02x ", bytes[i]);

}

// Output on little-endian x86-64: 2a 00 00 00This is the object representation, the actual bytes in memory. The semantic interpretation (that these bytes represent the integer 42) is layered on top by the type system.

Rust and C++ inherit this model. When we say a Rust i32 occupies 4 bytes with alignment 4, we mean exactly what C means: 4 contiguous bytes at an address divisible by 4. The type systems differ dramatically in what operations they permit on those bytes, but the physical representation is identical.

This is the starting point. We have bytes in a virtual address space, aligned for hardware access, managed by an allocator. Everything that follows (effective types, ownership, lifetimes) is a layer of abstraction over this physical reality.

From Bytes to Objects

A region of memory becomes an object when we impose a type interpretation on it. The type dictates how many bytes participate, what their alignment must be, and what operations are valid. But the three languages differ fundamentally in when and how this imposition occurs, and what invariants the type carries.

C: Effective Type Rules

In C, the relationship between memory and type is established through the concept of effective type. The effective type of an object determines how it may be accessed.

For declared variables, the effective type is simply the declared type:

int x = 42; // effective type of x is intThe variable x occupies sizeof(int) bytes at some address, and those bytes must be accessed as int or as unsigned char. Accessing them as float* is undefined behavior:

int x = 42;

float *fp = (float *)&x;

float f = *fp; // undefined behavior: access through incompatible typeThis is not a runtime check. The compiler does not insert code to verify the access. Instead, the rule exists to enable optimization. When the compiler sees a write through int* and a read through float*, the strict aliasing rule permits it to assume these pointers reference different objects. The compiler can then reorder loads and stores, keep values in registers across the write, and eliminate redundant accesses.

The rule has a critical asymmetry. Any object can be viewed as an array of unsigned char:

int x = 42;

unsigned char *bytes = (unsigned char *)&x;

for (size_t i = 0; i < sizeof(int); i++) {

printf("%02x ", bytes[i]); // valid: char access is always permitted

}But the reverse is undefined:

unsigned char buffer[sizeof(int)] = {0};

int *p = (int *)buffer;

int val = *p; // undefined behaviorThe buffer’s effective type is unsigned char[4]. Accessing it through int* violates the effective type rule. The fact that the bytes happen to form a valid int representation is irrelevant. The compiler is entitled to assume this access cannot happen, and may generate code that produces garbage or crashes.

For dynamically allocated memory, the situation is different. Memory returned by malloc has no effective type until we write to it:

void *p = malloc(sizeof(double));

double *dp = p;

*dp = 3.14; // this write sets the effective type to doubleAfter this write, the allocated region has effective type double. Subsequent reads through double* are valid. Reading through int* would again be undefined.

The effective type machinery exists purely for optimization. The compiler uses it to reason about aliasing. It provides no runtime safety.

C++: Object Lifetime

C++ inherits C’s effective type rules but adds a distinct concept: object lifetime. An object’s lifetime is the interval during which accessing the object is well-defined.

The C++ standard specifies the boundaries precisely. For an object of type T, lifetime begins when storage with proper alignment and size is obtained and initialization (if any) is complete. Lifetime ends when the destructor call starts (for class types) or when the object is destroyed (for non-class types), or when the storage is released or reused.

Consider placement new:

struct Widget {

int value;

Widget(int v) : value(v) { }

~Widget() { std::cout << "destroyed\n"; }

};

alignas(Widget) unsigned char buffer[sizeof(Widget)];

Widget* w = new (buffer) Widget(42); // lifetime begins here

w->~Widget(); // lifetime ends here

// buffer still contains bytes, but no Widget object existsBetween placement new and the destructor call, a Widget object exists at that address. Before placement new and after the destructor, the bytes exist but no Widget does. Accessing w->value after w->~Widget() is undefined behavior, even though the bytes are still there and unchanged.

The destructor call does not free memory. It ends the object’s lifetime while the storage remains intact. This is what placement new and explicit destructor calls rely on: the ability to construct an object in pre-existing storage, use it, destroy it, and potentially construct a different object in the same storage.

For trivial types (those without constructors, destructors, or virtual functions), C++ objects behave essentially like C objects. For class types with nontrivial special member functions, the lifetime boundaries become significant. A std::string accessed after destruction will likely read freed memory or corrupted pointers, because the destructor deallocated the internal buffer.

C++20 also introduced implicit object creation. Certain operations, such as std::malloc, implicitly create objects of implicit-lifetime types if doing so would give the program defined behavior:

struct Point { int x, y; }; // implicit-lifetime type (trivial)

Point* p = (Point*)std::malloc(sizeof(Point));

p->x = 1; // in C++20, this is well-defined

p->y = 2; // malloc implicitly created the Point objectThis was added to retroactively make well-defined the code patterns that had been common but technically undefined.

Rust: Validity Invariants

Rust imposes a stronger requirement. Every type has validity invariants, and producing a value that violates its type’s invariant is immediate undefined behavior. The compiler’s optimizer assumes these invariants hold unconditionally.

The Rust Reference defines validity per type:

// A bool must be 0x00 (false) or 0x01 (true)

let b: bool = unsafe { std::mem::transmute(2u8) }; // UB: invalid bool

// A reference must be non-null, aligned, and point to a valid value

let r: &i32 = unsafe { std::mem::transmute(0usize) }; // UB: null reference

// A char must be a valid Unicode scalar value (not a surrogate)

let c: char = unsafe { std::mem::transmute(0xD800u32) }; // UB: surrogate

// An enum must have a valid discriminant

enum Status { Active = 0, Inactive = 1 }

let s: Status = unsafe { std::mem::transmute(2u8) }; // UB: invalid discriminant

// The never type must never exist

let n: ! = unsafe { std::mem::zeroed() }; // UBThe moment an invalid value is produced, undefined behavior has occurred. The Rust compiler assumes that all values produced during program execution are valid; producing an invalid value is therefore immediate UB.

In C, you can have an int variable containing any 32-bit pattern, and as long as you do not read it in certain ways, no UB occurs. In Rust, if a bool contains the bit pattern 0x02, UB has already happened at the point of creation, regardless of whether you subsequently read it.

Consider references. In C and C++, a pointer can be null, and dereferencing it is UB. But the pointer itself can exist and be passed around. In Rust:

let ptr: *const i32 = std::ptr::null(); // valid: raw pointer can be null

let r: &i32 = unsafe { &*ptr }; // UB occurs HERE, at reference creationThe UB does not occur when we read through the reference. It occurs when the reference is created. A &T carries an invariant: non-null, properly aligned, pointing to a valid T. Violating this invariant at any point is UB, regardless of what we do with the reference afterward.

This strictness enables more aggressive optimization. When the compiler sees a &T, it emits dereferenceable and nonnull annotations to LLVM. A match expression on a bool need not generate a default case for values 2-255. These optimizations would be unsound if invalid values could exist.

The cost is that more operations require unsafe. You cannot create a reference to potentially-invalid memory, even temporarily. You must use raw pointers and convert to references only when validity is guaranteed:

let ptr: *const i32 = some_ffi_function();

if !ptr.is_null() && ptr.is_aligned() {

let r: &i32 = unsafe { &*ptr }; // sound: we verified validity

println!("{}", *r);

}Object Representation vs. Value

All three languages distinguish between an object’s representation (its bytes in memory) and its value (the semantic interpretation of those bytes). But they draw the line differently, and understanding where each language draws it determines what low-level manipulations are sound.

Every object occupies a contiguous sequence of bytes. The size of a type is how many bytes; the alignment constrains where those bytes can start. A type with alignment 8 must be stored at an address divisible by 8. These constraints reflect how the memory bus fetches data, as we saw in the alignment section.

In C, we can freely inspect any object as unsigned char[]:

double d = 3.14159;

unsigned char *bytes = (unsigned char *)&d;

// bytes[0..7] contain the IEEE 754 representationThe bytes are the representation. The value is what those bytes mean according to IEEE 754. C permits examining bytes without caring about their semantic meaning. C++ inherits this but adds constraints around object lifetime: we can inspect the bytes of a live object, but accessing bytes after the destructor has run is undefined, even if the storage has not been reused.

Rust permits byte-level inspection through raw pointers and transmutation, but imposes validity constraints that C and C++ do not:

let x: i32 = 42;

let bytes: [u8; 4] = unsafe { std::mem::transmute(x) };

// bytes contains the little-endian representation: [42, 0, 0, 0]

// Going the other direction requires care:

let bytes: [u8; 1] = [2];

let b: bool = unsafe { std::mem::transmute(bytes) }; // UB: 2 is not a valid boolThe asymmetry mirrors C’s effective type rule. Converting a typed value to bytes is generally safe. Converting bytes to a typed value requires that the bytes constitute a valid value of that type, and Rust’s validity invariants, as we saw earlier, are stricter than C’s.

This distinction matters when we consider struct layout. C guarantees fields appear in declaration order; the compiler inserts padding but cannot reorder. C++ inherits this for standard-layout types. Rust makes minimal guarantees by default: the repr(Rust) layout allows the compiler to reorder fields to minimize padding. Consider:

struct A {

a: u8,

b: u32,

c: u16,

}Rust might lay this out as (b, c, a, padding) to achieve size 8 instead of the naive 12. Different generic instantiations of the same struct may have different layouts. For interoperability with C, Rust provides #[repr(C)], which guarantees C-compatible layout: fields in declaration order, padding computed by the standard algorithm.

The layout algorithm for repr(C) is deterministic. Start with offset 0. For each field in declaration order: add padding until the offset is a multiple of the field’s alignment, record the field’s offset, advance by the field’s size. Finally, round the struct’s total size up to its alignment. This is exactly how our struct Bad ended up at 24 bytes while struct Good achieved 16. The algorithm is mechanical, but field ordering is our responsibility.

When is mem::transmute sound? Size must match (the compiler enforces this). Alignment must be compatible: transmuting &u8 to &u64 is unsound even if sizes matched, because the u8 may not be 8-byte aligned. And validity must be preserved: the bytes must constitute a valid value of the target type. This last constraint is what Rust adds beyond C. The repr(transparent) attribute creates a type with identical layout to its single non-zero-sized field, making transmutation between them sound and enabling zero-cost newtypes.

Storage Duration

Every object resides somewhere in memory. The storage duration of an object determines when that memory is allocated and when it becomes invalid. All three languages recognize the same fundamental categories, though they use different terminology and provide different guarantees about deallocation.

The Four Categories

C defines four storage durations. C++ inherits the same four. Rust maps onto an equivalent model, though the language specification does not use identical terminology.

-

Static storage duration: The object exists for the entire execution of the program. In C and C++, this includes global variables, variables declared with

static, and string literals. In Rust, this includesstaticitems and string literals (which have type&'static str). The memory for these objects is typically placed in the.dataor.rodatasegment of the executable and requires no runtime allocation. -

Thread storage duration: The object exists for the lifetime of a thread. C11 introduced

_Thread_local(spelledthread_localsince C23), C++11 introducedthread_local, and Rust providesthread_local!macro. Each thread gets its own instance of the variable, allocated when the thread starts and deallocated when it terminates. -

Automatic storage duration: The object exists within a lexical scope, typically a function body or block. When execution enters the scope, space is reserved; when execution leaves, the space is released. In C and C++, local variables without

staticorthread_localhave automatic storage. In Rust, all local bindings have automatic storage. This is typically implemented via the stack. -

Allocated (dynamic) storage duration: The object’s lifetime is controlled explicitly by the program. In C, this means

malloc/free. In C++, this meansnew/deleteor allocator-aware containers. In Rust, this meansBox,Vec,String, and other heap-allocating types.

Stack

Automatic storage is almost universally implemented using a call stack. When a function is called, the compiler reserves space for its local variables by adjusting the stack pointer. On x86-64 following the System V ABI, this looks like:

my_function:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 48 ; reserve 48 bytes for locals

; ... function body ...

mov rsp, rbp

pop rbp

retThe sub rsp, 48 instruction allocates space for all local variables in a single operation. The compiler computes the required size at compile time by summing the sizes of all locals (accounting for alignment). Deallocation is equally cheap: mov rsp, rbp releases all that space instantly.

This has two consequences. First, allocation and deallocation of automatic storage is regardless of how many objects are involved. A function with 100 local variables pays the same cost as one with 2. Second, the space is not initialized. After sub rsp, 48, those 48 bytes contain whatever was previously on the stack. In C, reading an uninitialized automatic variable is undefined behavior (the value is indeterminate). In C++, the same rule applies. In Rust, the compiler enforces definite initialization: you cannot read a variable before assigning to it.

In C, reading an uninitialized automatic variable is undefined behavior (the value is indeterminate). In C++ prior to C++26, the same rule applies. C++26 introduces erroneous behavior, a new category: the value is still indeterminate but reading it is not UB—implementations may diagnose or zero-initialize. Clang’s

-ftrivial-auto-var-init=zerohas provided this behavior for years.

fn example() {

let x: i32;

println!("{}", x); // error: borrow of possibly-uninitialized variable

}The Rust compiler tracks initialization state through control flow and rejects programs that might read uninitialized memory. This is a compile-time check with no runtime cost.

Heap

Dynamic allocation is fundamentally different. When we call malloc(n), the allocator must find a contiguous region of at least n bytes that is not currently in use, mark that region as allocated, and return a pointer to it. When we call free(p), the allocator must determine the size of the allocation (stored in metadata adjacent to the user data), mark that region as available for future allocations, and possibly coalesce adjacent free regions to reduce fragmentation.

This involves data structure manipulation, potential system calls (if the allocator needs more memory from the OS), and can have variable latency depending on heap state. The cost is not .

In C, heap allocation is explicit:

int* p = malloc(sizeof(int) * 100);

if (p == NULL) {

// allocation failed

}

// ... use p ...

free(p);We are responsible for checking for allocation failure, calling free exactly once, not using the pointer after free, and not freeing the same pointer twice. Violating any of these causes undefined behavior or memory leaks. The language provides no assistance.

In C++, dynamic allocation can be explicit (new/delete) or managed through RAII:

// Explicit (dangerous)

int* p = new int[100];

delete[] p;

// RAII (safer)

auto v = std::make_unique<int[]>(100);

// v automatically deleted when it goes out of scopestd::unique_ptr wraps a raw pointer and calls delete in its destructor. When v goes out of scope, the destructor runs, the memory is freed. We do not call delete manually.

This is opt-in. You can still use raw new/delete. You can still have dangling pointers. The compiler does not verify correctness.

In Rust, heap allocation is handled through owning types:

let v: Vec<i32> = Vec::with_capacity(100);

// v automatically deallocated when it goes out of scopeVec<T> owns heap-allocated memory. When v goes out of scope, Vec’s Drop implementation runs, calling the allocator to free the buffer. There is no way to forget to free, no way to double-free, and no way to use after free (the compiler rejects such programs).

The difference from C++ is that Rust’s ownership is not opt-in. Every heap allocation is owned by exactly one binding. Transferring ownership is a move. After a move, the original binding is unusable:

let v1 = vec![1, 2, 3];

let v2 = v1; // v1 moved to v2

println!("{:?}", v1); // error: borrow of moved valueWho Calls Free?

The central difference between C, C++, and Rust in their treatment of dynamic storage is responsibility for deallocation.

In C, we decide when to call free. The language does not track ownership. If you pass a pointer to a function, the function might free it, or it might not. The only way to know is documentation or convention.

void process(int* data) {

// Does this function free data? You have to read the docs.

}In C++, RAII shifts responsibility to destructors. If you use unique_ptr, the destructor frees. If you use shared_ptr, the destructor decrements a reference count and frees when it reaches zero. But you can still use raw pointers, and the compiler cannot tell you which convention a given codebase follows.

void process(int* data) {

// Raw pointer: who owns this? Still ambiguous.

}

void process(std::unique_ptr<int[]> data) {

// Ownership transferred: this function will free when done.

}In Rust, the type system encodes ownership:

fn process(data: Vec<i32>) {

// This function owns data. It will be freed when process returns.

}

fn process_ref(data: &Vec<i32>) {

// This function borrows data. The caller retains ownership.

}

fn process_mut(data: &mut Vec<i32>) {

// Mutable borrow. Caller retains ownership. No other access allowed during this call.

}The signature tells you everything. Vec<i32> means ownership transfer. &Vec<i32> means immutable borrow. &mut Vec<i32> means mutable borrow. The compiler enforces these semantics. You cannot pass a Vec and then continue using it; the move would be rejected.

Stack Allocation in Rust

Rust provides fine-grained control over whether data lives on the stack or heap. By default, local bindings are stack-allocated:

let x: [i32; 1000] = [0; 1000]; // 4000 bytes on the stackThis works until the array is too large for the stack (typically 1-8 MB depending on platform). For large allocations, use Box:

let x: Box<[i32; 1000000]> = Box::new([0; 1000000]); // heapBox<T> is a pointer to a heap allocation. It has the same size as a raw pointer (8 bytes on 64-bit), implements Deref so you can use it like a reference, and frees the allocation in its Drop implementation.

The memory layout of Box<T> is a single pointer:

use std::mem::size_of;

assert_eq!(size_of::<Box<[i32; 1000]>>(), 8); // just a pointerUnlike C++ unique_ptr, which may carry a deleter, Box<T> always uses the global allocator and has no space overhead. The deallocation function is known statically.

Object Lifetime

Storage duration determines when memory is allocated and deallocated. Object lifetime determines when accessing that memory is well-defined. In C, these are identical. In C++, they can differ. In Rust, lifetime becomes a compile-time property tracked through constraint propagation over the control-flow graph.

C: Lifetime Is Storage Duration

C does not distinguish between storage exists and object is alive. An object with automatic storage duration is alive from when execution enters its block of definition until execution leaves. An object with static storage duration is alive for the entire program. An object with allocated storage duration is alive from malloc to free.

The consequence is that C has no notion of storage exists but object is not yet constructed. When the stack frame is created, all automatic variables exist. Whether they are initialized is a separate question:

int* dangling(void) {

int x = 42;

return &x;

}

int main(void) {

int* p = dangling();

printf("%d\n", *p); // undefined behavior

}This program compiles. The function dangling returns a pointer to x, but x has automatic storage duration. When dangling returns, its stack frame is deallocated. The pointer p now points to memory that no longer belongs to any live object. Dereferencing it is undefined behavior.

The C standard does not require the compiler to reject this. A conforming implementation may emit a warning, but the program is syntactically valid. The burden falls entirely on us.

C++: Lifetime Within Storage

C++ introduces a distinction. Storage duration determines when memory is allocated and deallocated. Object lifetime determines when the object can be accessed. For class types, lifetime begins when the constructor completes and ends when the destructor starts.

Consider placement new:

struct Widget {

std::string name;

Widget(const char* n) : name(n) { }

~Widget() { std::cout << "destroyed\n"; }

};

alignas(Widget) unsigned char buffer[sizeof(Widget)];

// Storage exists. No Widget object exists.

Widget* w = new (buffer) Widget("test");

// Constructor has run. Widget object now exists.

w->~Widget();

// Destructor has run. Widget object no longer exists.

// Storage still exists.Between placement new and the explicit destructor call, the Widget object is alive. Before placement new and after the destructor, the bytes in buffer exist but no Widget does. Accessing w->name after the destructor call is undefined behavior. The bytes are there. The object is not.

The C++ standard formalizes this. For an object of type T, lifetime begins when storage with proper alignment and size is obtained and initialization is complete. Lifetime ends when the destructor call starts (for class types) or when the object is destroyed (for non-class types).

For trivial types (no user-defined constructor, no destructor, no virtual functions), C++ behaves like C. For class types with nontrivial constructors or destructors, the distinction matters.

The dangling reference problem persists:

int& dangling() {

int x = 42;

return x;

}This compiles. A good compiler warns. The standard does not require rejection.

Rust: Lifetimes as Named Regions

Rust prevents dangling references through compile-time analysis. The equivalent code does not compile:

fn dangling() -> &i32 {

let x = 42;

&x

}The compiler rejects this:

error[E0106]: missing lifetime specifier

--> src/lib.rs:1:18

|

1 | fn dangling() -> &i32 {

| ^ expected named lifetime parameterWe cannot return a reference without specifying its lifetime. If we try to add one:

fn dangling<'a>() -> &'a i32 {

let x = 42;

&x

}error[E0515]: cannot return reference to local variable `x`

--> src/lib.rs:3:5

|

3 | &x

| ^^ returns a reference to data owned by the current functionThe compiler determines that x does not live long enough to satisfy the lifetime 'a. How does it know this? The answer lies in region inference.

Regions and the Control-Flow Graph

A lifetime in Rust is a region: a set of points in the control-flow graph where a reference must be valid. The borrow checker computes these regions through constraint propagation.

Consider this code:

let x = 0;

let y = &x;

let z = &y;Each let binding introduces an implicit scope. The borrow checker infers the minimal region for each reference. Desugared (using notation that is not valid Rust syntax, but illustrates the structure):

'a: {

let x: i32 = 0;

'b: {

let y: &'b i32 = &'b x;

'c: {

let z: &'c &'b i32 = &'c y;

}

}

}The reference y has lifetime 'b because that is the smallest region that covers its usage. The reference z has lifetime 'c. The borrow checker minimizes lifetimes to the extent necessary.

When a reference is passed to an outer scope, the borrow checker infers a larger lifetime:

let x = 0;

let z;

let y = &x;

z = y;Desugared:

'a: {

let x: i32 = 0;

'b: {

let z: &'b i32;

'c: {

let y: &'b i32 = &'b x; // must use 'b, not 'c

z = y;

}

}

}Because y is assigned to z, and z lives in scope 'b, the reference must be valid for 'b. The borrow checker propagates this requirement.

Region Inference in rustc

The borrow checker operates on MIR (Mid-level Intermediate Representation), a simplified form of Rust code. The process has two phases:

Phase 1: replace_regions_in_mir

The compiler identifies universal regions (those appearing in the function signature, such as 'a in fn foo<'a>(x: &'a u32)) and replaces all other regions with fresh inference variables. Universal regions are free in the function body. They represent constraints from the caller.

Phase 2: compute_regions

The compiler runs a type checker on MIR to collect constraints between regions. It then performs constraint propagation to compute the value of each inference variable.

A region’s value is a set. The set contains:

-

Locations in the MIR control-flow graph: Each location is a pair (basic block, statement index). This identifies the point on entry to that statement.

-

End markers for universal regions: If region

'aoutlives region'b, thenend('b)is in the set for'a. The elementend('b)represents the portion of the caller’s control-flow graph after the current function returns. -

end('static): Represents program execution after the function returns, extending to program termination.

The two main constraint types are:

Outlives constraints: If 'a: 'b (region 'a outlives region 'b), all elements of 'b plus end('b) must be added to 'a.

Liveness constraints: A region must contain all points where it can be used.

Constraint Propagation

Consider this function:

fn bad<'a, 'b>(x: &'a usize) -> &'b usize {

x

}This should not compile. We have no guarantee that 'a outlives 'b. If 'a is shorter than 'b, the return value would be a dangling reference.

The compiler introduces inference variables. Let '#1 correspond to 'a, '#3 correspond to 'b, and '#2 correspond to the expression x. Let L1 be the location of x.

Initial state from liveness constraints:

| Region | Contents |

|---|---|

| ’#1 | (empty) |

| ‘#2 | L1 |

| ’#3 | L1 |

The return statement creates an outlives constraint '#2: '#3 (the returned reference must outlive the return type’s region). Propagating:

| Region | Contents |

|---|---|

| ’#1 | L1 |

| ’#2 | L1, end(‘#3) |

| ‘#3 | L1 |

The parameter creates an outlives constraint '#1: '#2 (the input flows to the expression). Propagating:

| Region | Contents |

|---|---|

| ’#1 | L1, end(‘#2), end(‘#3) |

| ‘#2 | L1, end(‘#3) |

| ‘#3 | L1 |

Now the compiler checks: does '#1 contain any end('x) that is not justified by a where clause or implied bound? Yes. '#1 contains end('#3), but we have no where clause stating 'a: 'b. This is an error.

The RegionInferenceContext in rustc stores:

constraints: all outlives constraintsliveness_constraints: all liveness constraintsuniversal_regions: the set of regions from the function signatureuniversal_region_relations: known relationships between universal regions (from where clauses)

The solve method performs propagation, then check_universal_regions verifies that no universal region grew to contain end markers it cannot justify.

Non-Lexical Lifetimes

Before Rust 2018, lifetimes were lexical: a reference was live until the end of its lexical scope. This rejected valid programs:

let mut data = vec![1, 2, 3];

let x = &data[0];

println!("{}", x);

data.push(4); // error in old Rust: x still in scopeWith lexical lifetimes, x would be considered live until the closing brace, conflicting with the mutable borrow for push.

Non-lexical lifetimes (NLL) compute liveness from the control-flow graph. A reference is live from its creation to its last use, not to the end of its scope:

let mut data = vec![1, 2, 3];

let x = &data[0];

println!("{}", x); // last use of x

data.push(4); // ok: x is no longer liveThe borrow of data for x extends to the println! call. After that, the borrow ends. The mutable borrow for push does not conflict.

There are subtleties. If a type has a destructor, the destructor counts as a use. The destructor runs at scope end, extending the lifetime:

struct Wrapper<'a>(&'a i32);

impl Drop for Wrapper<'_> {

fn drop(&mut self) { }

}

let mut data = vec![1, 2, 3];

let x = Wrapper(&data[0]);

println!("{:?}", x);

data.push(4); // error: destructor of x runs at scope endThe Drop impl means x is used at scope end. The borrow extends to that point, conflicting with push. To fix this, we can call drop(x) explicitly before push.

Lifetimes can have holes. A variable can be reborrowed:

let mut data = vec![1, 2, 3];

let mut x = &data[0];

println!("{}", x); // last use of first borrow

data.push(4); // ok: first borrow ended

x = &data[3]; // new borrow starts

println!("{}", x);The borrow checker sees two distinct borrows tied to the same variable. The first ends after the first println!. The second starts at the reassignment.

Control flow matters. Different branches can have different last uses:

fn condition() -> bool { true }

let mut data = vec![1, 2, 3];

let x = &data[0];

if condition() {

println!("{}", x); // last use in this branch

data.push(4); // ok

} else {

data.push(5); // ok: x not used in this branch

}In the if branch, x is used before push. In the else branch, x is never used, so the borrow effectively ends at x’s creation.

Lifetimes Across Function Boundaries

Within a function, the borrow checker has complete information. It knows every use of every reference. Across function boundaries, this information is lost. Function signatures must declare the relationships between input and output lifetimes.

fn first_word(s: &str) -> &str {

// returns a slice of the input

}The signature says: the output lifetime equals the input lifetime. The returned slice borrows from s. Callers cannot use the returned slice after s is invalidated.

When signatures are ambiguous, the compiler requires explicit annotation:

fn longest(x: &str, y: &str) -> &str {

if x.len() > y.len() { x } else { y }

}This does not compile. The return could come from x or y. The compiler does not know which. We must tell it:

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str {

if x.len() > y.len() { x } else { y }

}The signature now says: both inputs must be valid for at least 'a, and the output is valid for 'a. Callers must ensure both inputs outlive the result.

Lifetime Elision

Common patterns do not require explicit annotation. Elision rules infer lifetimes:

Rule 1: Each input reference gets its own lifetime.

fn f(x: &i32, y: &i32)

// becomes

fn f<'a, 'b>(x: &'a i32, y: &'b i32)Rule 2: If there is exactly one input lifetime, it is assigned to all outputs.

fn f(x: &i32) -> &i32

// becomes

fn f<'a>(x: &'a i32) -> &'a i32Rule 3: If one input is &self or &mut self, its lifetime is assigned to all outputs.

impl Foo {

fn method(&self, x: &i32) -> &i32

// becomes

fn method<'a, 'b>(&'a self, x: &'b i32) -> &'a i32

}When elision rules do not determine all lifetimes, explicit annotation is required.

'static

The lifetime 'static means valid for the entire program remainder of program execution. String literals have type &'static str because they are stored in the binary’s read-only data segment:

let s: &'static str = "hello";The bound T: 'static means T contains no non-static references. This is required for spawning threads, since the spawned thread may outlive the current stack frame:

fn spawn<F>(f: F) where F: FnOnce() + Send + 'staticA closure that captures &x where x is a local variable does not satisfy 'static. The reference would dangle when the spawning function returns.

Uninitialized Memory

All runtime-allocated memory begins as uninitialized. The bytes exist but contain whatever values were left there by previous use. The question is: what happens when we read those bytes before writing to them?

C says the value is indeterminate. C++ adds the concept of vacuous initialization. Rust says reading uninitialized memory is undefined behavior, full stop, and provides MaybeUninit<T> as the controlled mechanism for working with such memory.

C: Indeterminate Values

In C, reading an uninitialized automatic variable produces an indeterminate value. The C23 standard distinguishes this from a non-value representation (previously called trap representation), which is a bit pattern that does not correspond to any valid value of the type.

void example(void) {

int x;

printf("%d\n", x); // indeterminate value

}What happens here? The standard does not say the program crashes. It does not say the program continues with some arbitrary value. It says the behavior is undefined. The compiler is permitted to assume this code never executes.

The distinction between indeterminate values and non-value representations matters for types where not all bit patterns are valid. The bool type has only two valid values: 0 (false) and 1 (true). A bool occupies at least 8 bits. Setting other bits produces a non-value representation:

bool b;

memset(&b, 0xFF, sizeof(b)); // all bits set

if (b) { /* ... */ } // undefined behaviorThe compiler may test for zero, or it may test the least significant bit. Different optimization levels may produce different results. The behavior is not merely unspecified (implementation-defined but consistent); it is undefined (the compiler may assume it cannot happen).

For types without non-value representations (most integer types on modern hardware), reading an indeterminate value is still undefined behavior because the compiler cannot reason about what value it will see. The optimizer may propagate contradictory assumptions through the program.

C++: Vacuous Initialization and Implicit Object Creation

C++ inherits C’s rules for scalar types but adds complexity for class types. A variable has vacuous initialization if it is default-initialized and its class type has a trivial default constructor.

struct Trivial {

int x;

int y;

};

void example() {

Trivial t; // vacuous initialization: x and y are indeterminate

}The object t exists. Its lifetime has begun. But its members x and y contain indeterminate values. Reading them is undefined behavior, just as in C.

For class types with nontrivial constructors, default initialization runs the constructor:

struct Nontrivial {

int x;

Nontrivial() : x(0) { }

};

void example() {

Nontrivial n; // constructor runs, x is 0

}C++20 introduced implicit object creation. Certain operations (allocation functions, memmove, memcpy, creation of unsigned char or std::byte arrays) implicitly create objects of implicit-lifetime types within their storage region. This retroactively makes some previously-undefined patterns well-defined:

struct X { int a, b; };

X* make_x() {

X* p = (X*)std::malloc(sizeof(struct X));

p->a = 1; // pre-C++20: UB (no X object exists)

p->b = 2; // C++20: ok (X implicitly created)

return p;

}The C++ standard specifies that malloc implicitly creates objects of implicit-lifetime types if doing so would give the program defined behavior. This was a pragmatic fix for code that had been written for decades under the assumption that malloc plus assignment creates an object.

Rust: Immediate Undefined Behavior

Rust takes the strictest position. Reading uninitialized memory is undefined behavior at the point of the read, regardless of type. The Rust Reference states that integers, floating point values, and raw pointers must be initialized and must not be obtained from uninitialized memory.

This applies even to u8, which has no invalid bit patterns. The reasoning is that the compiler must be able to assume all values are initialized. Without this guarantee, the optimizer cannot propagate values, eliminate dead stores, or make any assumptions about the contents of memory.

Rust enforces this at compile time for safe code through definite initialization analysis:

fn example() {

let x: i32;

println!("{}", x); // error: use of possibly uninitialized `x`

}The analysis tracks initialization state through control flow:

fn example(condition: bool) {

let x: i32;

if condition {

x = 1;

}

println!("{}", x); // error: `x` is possibly uninitialized

}Even though the if branch initializes x, the else branch does not. The compiler rejects the program.

The analysis understands control flow but not values:

fn example() {

let x: i32;

if true {

x = 1;

}

println!("{}", x); // error: compiler doesn't evaluate `true`

}The compiler does not evaluate true at analysis time. It sees a conditional with only one branch that initializes x. The program is rejected.

Loops require care:

fn example() {

let x: i32;

loop {

if true {

x = 0;

break;

}

}

println!("{}", x); // ok: compiler knows break is reached

}The compiler understands that execution cannot reach println! without passing through the break, and the break is preceded by initialization. The program compiles.

Move Semantics and Uninitialization

In Rust, moving a value out of a variable leaves that variable logically uninitialized:

fn example() {

let x = Box::new(42);

let y = x; // x is moved, now logically uninitialized

println!("{}", x); // error: use of moved value

}For Copy types, this does not apply. The value is copied, and both variables remain initialized:

fn example() {

let x: i32 = 42;

let y = x; // copy, not move

println!("{}", x); // ok: x is still initialized

}A variable can be reinitialized after being moved from:

fn example() {

let mut x = Box::new(42);

let y = x; // x is moved

x = Box::new(43); // x is reinitialized

println!("{}", x); // ok

}The mut is required because the compiler considers reinitialization to be mutation.

MaybeUninit<T>: The Escape Hatch

When performance requires working with uninitialized memory, Rust provides MaybeUninit<T>. This is a union type that can hold either an initialized T or uninitialized bytes:

use std::mem::MaybeUninit;

let x: MaybeUninit<i32> = MaybeUninit::uninit();The key property: dropping a MaybeUninit<T> does nothing. It does not run T’s destructor. This is essential because the value might not be initialized, and dropping an uninitialized value would be undefined behavior.

To initialize, we write to the MaybeUninit:

let mut x: MaybeUninit<i32> = MaybeUninit::uninit();

x.write(42); // now initializedTo extract the initialized value, we call assume_init:

let mut x: MaybeUninit<i32> = MaybeUninit::uninit();

x.write(42);

let value: i32 = unsafe { x.assume_init() };The assume_init call is unsafe because the compiler cannot verify that we actually initialized the value. We are asserting to the compiler: trust me, it is initialized. If we lied, behavior is undefined.

Array Initialization

Safe Rust does not permit partial array initialization. We must initialize all elements at once:

let arr: [i32; 4] = [1, 2, 3, 4]; // ok

let arr: [i32; 1000] = [0; 1000]; // ok, all zerosFor dynamic initialization, MaybeUninit provides a path:

use std::mem::{self, MaybeUninit};

const SIZE: usize = 10;

let arr: [Box<u32>; SIZE] = {

// Create array of uninitialized MaybeUninit

let mut arr: [MaybeUninit<Box<u32>>; SIZE] =

[const { MaybeUninit::uninit() }; SIZE];

// Initialize each element

for i in 0..SIZE {

arr[i] = MaybeUninit::new(Box::new(i as u32));

}

// Transmute to initialized type

unsafe { mem::transmute::<_, [Box<u32>; SIZE]>(arr) }

};The transmute is sound because MaybeUninit<T> has the same layout as T. We initialized every element, so the array now contains valid Box<u32> values.

A critical detail: the assignment arr[i] = MaybeUninit::new(...) does not drop the old value. MaybeUninit<T> has no Drop implementation. If we had written to a regular Box<u32> array, the assignment would drop the old value, which would be undefined behavior for uninitialized memory.

Raw Pointer Writes

When MaybeUninit::new is not suitable, we use raw pointer operations. The ptr module provides:

ptr::write(ptr, val): Writesvaltoptrwithout reading or dropping the old valueptr::copy(src, dest, count): Copiescountelements fromsrctodest(likememmove)ptr::copy_nonoverlapping(src, dest, count): Likecopy, but assumes no overlap (likememcpy)

These functions do not drop the destination. They overwrite the bytes. This is correct for uninitialized memory but dangerous for initialized memory containing values with destructors. We can use std::mem::needs_drop::<T>() to check at compile time whether a type requires drop glue.

A subtlety: the destination pointer must have provenance for the target allocation. Rust’s memory model tracks not just addresses but also which allocation a pointer is permitted to access. A pointer synthesized from an integer (via ptr::from_exposed_addr)

has weaker provenance guarantees than one derived from a reference.

use std::ptr;

let mut x: MaybeUninit<String> = MaybeUninit::uninit();

unsafe {

ptr::write(x.as_mut_ptr(), String::from("hello"));

}

let s = unsafe { x.assume_init() };We cannot use &mut to get a reference to the uninitialized String because creating a reference to an invalid value is undefined behavior. The as_mut_ptr method returns a raw pointer without creating a reference.

For struct fields, we use raw reference syntax to avoid creating intermediate references:

use std::{ptr, mem::MaybeUninit};

struct Demo {

field: bool,

}

let mut uninit = MaybeUninit::<Demo>::uninit();

let field_ptr = unsafe { &raw mut (*uninit.as_mut_ptr()).field };

unsafe { field_ptr.write(true); }

let demo = unsafe { uninit.assume_init() };The &raw mut syntax creates a raw pointer without creating a reference. This is important because &mut (*uninit.as_mut_ptr()).field would create a reference to an uninitialized bool, which is undefined behavior.

The Vec Pattern

The most common use of uninitialized memory in Rust is building collections. Vec<T> internally uses MaybeUninit (via RawVec) to manage its buffer. When we call vec.reserve(n), the vector allocates space for n additional elements without initializing them.

A performance pattern for filling a vector from an external source:

fn read_into_vec(src: &[u8], count: usize) -> Vec<u8> {

let mut v: Vec<u8> = Vec::with_capacity(count);

unsafe {

// Get raw pointer to uninitialized buffer

let ptr = v.as_mut_ptr();

// Copy from source (assumes src.len() >= count)

std::ptr::copy_nonoverlapping(src.as_ptr(), ptr, count);

// Tell Vec the elements are now initialized

v.set_len(count);

}

v

}The set_len call is unsafe because we are asserting that the first count elements are initialized. The vector trusts us. If we lie, dropping the vector will attempt to drop uninitialized values, which is undefined behavior for types with destructors.

For u8, there is no destructor, so the immediate danger is reading garbage. But the compiler may still optimize based on the assumption that all values are initialized.

The safe alternative uses resize or extend:

fn read_into_vec_safe(src: &[u8], count: usize) -> Vec<u8> {

let mut v: Vec<u8> = Vec::with_capacity(count);

v.extend_from_slice(&src[..count]);

v

}This initializes each element as it is added. For large buffers, the unsafe version can be measurably faster because it avoids redundant initialization. Whether the speedup matters depends on the workload.

The Deprecated mem::uninitialized

Older Rust code uses mem::uninitialized::<T>() to create uninitialized values. This function is deprecated and should not be used in new code. The problem is that it returns a T, which means the caller receives an initialized value of type T that actually contains garbage:

// DON'T DO THIS

let x: bool = unsafe { std::mem::uninitialized() };

// x is now an "initialized" bool with garbage bits

// Any use of x is undefined behaviorThe compiler believes x is initialized. It may propagate this “value” through the program. The result is unpredictable.

MaybeUninit solves this by wrapping the uninitialized state in a type that the compiler understands. The value inside is not accessible until we call assume_init. This prevents the compiler from making false assumptions about initialization state.

Aliasing

Two pointers alias when they refer to overlapping regions of memory. This matters because aliasing constrains what the compiler can optimize. If the compiler cannot prove that two pointers refer to different memory, it must assume that a write through one may affect a read through the other. This forces conservative code generation: values must be reloaded from memory instead of kept in registers, stores cannot be reordered, and entire classes of optimization become impossible.

Aliasing rules exist for optimization, not for safety. C and C++ have aliasing rules that, when violated, result in undefined behavior. The compiler is not checking these rules to protect us. It is assuming we follow them, and optimizing accordingly. Violate the assumption and the optimizer generates incorrect code.

Rust makes the aliasing rule explicit and compiler-checked. The &T/&mut T distinction encodes a simple invariant: you can have many shared references or one mutable reference, but never both simultaneously. The borrow checker enforces this at compile time.

Why the Compiler Cares

Consider this function:

fn compute(input: &u32, output: &mut u32) {

if *input > 10 {

*output = 1;

}

if *input > 5 {

*output *= 2;

}

}We would like the compiler to optimize this to:

fn compute(input: &u32, output: &mut u32) {

let cached_input = *input;

if cached_input > 10 {

*output = 2;

} else if cached_input > 5 {

*output *= 2;

}

}The optimization caches *input in a register and eliminates the redundant read in the second condition. It also recognizes that if *input > 10, the final value will always be 2 (set to 1, then doubled), so it writes 2 directly.

This optimization is only valid if input and output do not alias. If they point to the same memory, the write *output = 1 changes what *input reads:

let mut x: u32 = 20;

compute(&x, &mut x); // input and output both point to xWith aliasing, the original function produces 1:

*inputis 20, so*output = 1(nowxis 1)*inputis 1, so the second condition is false- Result: 1

The optimized function produces 2:

cached_inputis 20, so*output = 2- Result: 2

In Rust, the call compute(&x, &mut x) is rejected at compile time. The borrow checker sees an attempt to create both a shared reference and a mutable reference to x simultaneously. The program does not compile.

In C, the equivalent code compiles and the optimizer may generate the wrong result.

C: Type-Based Alias Analysis

The C standard specifies the effective type rule. An object must be accessed through its effective type or through a character type. Accessing an object through a pointer of incompatible type is undefined behavior.

int x = 42;

float* fp = (float*)&x;

float f = *fp; // undefined behavior: accessing int through float*This is often called strict aliasing. The compiler assumes that pointers of different types do not alias. An int* and a float* cannot point to the same object (with narrow exceptions for character types and unions). This assumption enables Type-Based Alias Analysis (TBAA): the compiler tracks pointer types and assumes incompatible types refer to disjoint memory.

Consider:

void update(int* pi, float* pf) {

*pi = 1;

*pf = 2.0f;

printf("%d\n", *pi);

}Under strict aliasing, the compiler may assume pi and pf do not alias. The write to *pf cannot affect *pi, so the compiler can print 1 without reloading from memory. It may even reorder the stores or keep *pi in a register.

If we pass pointers that actually alias:

union { int i; float f; } u;

update(&u.i, &u.f); // undefined behaviorThe optimizer’s assumption is violated. The generated code may print 1 even though the memory now contains the bit pattern of 2.0f. Or it may print something else entirely. The behavior is undefined.

The classic strict aliasing violation involves type punning without unions:

uint32_t float_bits(float f) {

return *(uint32_t*)&f; // undefined behavior

}This attempts to read the bit representation of a float by casting its address to uint32_t*. The effective type of the object is float. Accessing it through uint32_t* violates the effective type rule.

The correct approach uses a union:

uint32_t float_bits(float f) {

union { float f; uint32_t u; } converter = { .f = f };

return converter.u;

}Or memcpy:

uint32_t float_bits(float f) {

uint32_t result;

memcpy(&result, &f, sizeof(result));

return result;

}Modern compilers optimize memcpy of small sizes to register moves. The resulting assembly is identical to the undefined type-punning version, but the semantics are well-defined.

The restrict Qualifier

Type-based alias analysis only helps when pointer types differ. Two int* pointers may alias, and the compiler must assume they do unless told otherwise.

C99 introduced the restrict qualifier. A restrict-qualified pointer is a promise from us: during the lifetime of this pointer, no other pointer will be used to access the same memory.

void add_arrays(int* restrict dest, const int* restrict src, size_t n) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; i++) {

dest[i] += src[i];

}

}The restrict qualifier tells the compiler that dest and src do not overlap. The compiler can vectorize the loop, load multiple elements of src at once, and store multiple elements to dest without worrying that a store to dest[i] might affect a subsequent load from src[j].

Without restrict:

void add_arrays(int* dest, const int* src, size_t n) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; i++) {

dest[i] += src[i];

}

}The compiler must assume dest and src might overlap. If dest == src + 1, each store to dest[i] affects the next load from src[i+1]. The loop cannot be vectorized. Each iteration must complete before the next begins.

The restrict qualifier is a promise, not a constraint. The compiler does not check it. If we lie and pass overlapping pointers, the optimized code produces wrong results.

Standard library functions use restrict extensively:

void* memcpy(void* restrict dest, const void* restrict src, size_t n);

void* memmove(void* dest, const void* src, size_t n);memcpy promises non-overlapping regions. memmove handles overlap correctly but cannot be optimized as aggressively.

Rust: Shared XOR Mutable

Rust’s aliasing model is simpler and compiler-enforced. The rule is: at any point in time, a piece of memory can have either many shared references (&T) or one mutable reference (&mut T), but not both.

This is sometimes written as shared XOR mutable, or aliasing XOR mutation. The key insight is that aliasing is only dangerous when combined with mutation. Many readers can safely read the same memory. A single writer can safely modify memory if no one else is reading. The problem arises when reads and writes can interleave unpredictably.

let mut x = 5;

let r1 = &x; // shared reference

let r2 = &x; // another shared reference, ok

println!("{} {}", r1, r2);

let r3 = &mut x; // mutable reference

*r3 += 1;

println!("{}", r3);This compiles because the shared references r1 and r2 are no longer used after the println!. Their lifetimes end before the mutable reference r3 is created.

let mut x = 5;

let r1 = &x;

let r3 = &mut x; // error: cannot borrow `x` as mutable

println!("{}", r1);This does not compile. The shared reference r1 is still live when we attempt to create the mutable reference r3. The borrow checker rejects the program.

The Rust compiler annotates references with LLVM attributes based on this invariant. A &T receives noalias for read operations. A &mut T receives noalias unconditionally, telling LLVM that no other pointer accesses this memory for the reference’s lifetime. This enables the same optimizations that C achieves through restrict, but the guarantee is compiler-verified rather than programmer-promised.

What the Borrow Checker Sees

The borrow checker does not understand the semantic meaning of operations. It does not know that &data[0] and &data[1] are disjoint. It sees borrows and tracks their lifetimes.

Consider this code that the borrow checker rejects:

let mut v = vec![1, 2, 3];

let x = &v[0]; // immutable borrow of v

v.push(4); // mutable borrow of v for push

println!("{}", x);The borrow checker sees that &v[0] creates a reference with some lifetime, that this reference x must live until println!, that v.push(4) requires &mut v, that at the point of push the reference x is still live, and therefore there is a conflict: we cannot have &mut v while &v exists.

The borrow checker does not know that push might reallocate the vector, invalidating x. It simply enforces the aliasing rule. As a consequence, it prevents the iterator invalidation bug.

The borrow checker also does not understand that &mut v[0] and &mut v[1] are disjoint:

let mut arr = [1, 2, 3];

let a = &mut arr[0];

let b = &mut arr[1]; // error: cannot borrow `arr[_]` as mutable more than onceThe indexing operation arr[i] desugars to a method call that borrows the entire array. The borrow checker sees two mutable borrows of arr, not two borrows of disjoint elements.

Splitting Borrows

The borrow checker understands struct fields as disjoint:

struct Point { x: i32, y: i32 }

let mut p = Point { x: 0, y: 0 };

let px = &mut p.x;

let py = &mut p.y; // ok: different fields

*px = 1;

*py = 2;This works because the compiler knows that p.x and p.y occupy different memory. They can be borrowed mutably at the same time.

For slices and arrays, the standard library provides split_at_mut:

let mut arr = [1, 2, 3, 4];

let (left, right) = arr.split_at_mut(2);

// left is &mut [1, 2], right is &mut [3, 4]

left[0] = 10;

right[0] = 30;The implementation of split_at_mut uses unsafe code:

pub fn split_at_mut(&mut self, mid: usize) -> (&mut [T], &mut [T]) {

let len = self.len();

let ptr = self.as_mut_ptr();

assert!(mid <= len);

unsafe {

(std::slice::from_raw_parts_mut(ptr, mid),

std::slice::from_raw_parts_mut(ptr.add(mid), len - mid))

}

}The unsafe block constructs two mutable slices from raw pointers. We assert that the slices do not overlap. The safe interface guarantees this by construction: the slices cover [0, mid) and [mid, len). This is a very Rusty pattern: building safe abstractions over unsafe primitives. Users of split_at_mut cannot violate the aliasing rules. The borrow checker verifies that the two returned slices are used correctly.

From Rules to Registers

We saw that aliasing information lets the compiler keep values in registers instead of reloading from memory. But the payoff extends beyond eliminating redundant loads. Consider what happens when the compiler tries to vectorize a loop.

void scale(float* dest, const float* src, float factor, size_t n) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; i++) {

dest[i] = src[i] * factor;

}

}If dest and src might overlap, each iteration depends on the previous. A write to dest[i] might modify src[i+1]. The compiler must execute iterations sequentially:

.loop:

movss xmm1, [rsi] ; load one float from src

mulss xmm1, xmm0 ; multiply by factor

movss [rdi], xmm1 ; store one float to dest

add rsi, 4

add rdi, 4

dec rcx

jnz .loopOne element per iteration. Almost any modern x86-64 CPU has 256-bit AVX registers that can hold eight floats. We are using 32 bits of that capacity. The other 224 bits sit idle.

Add restrict to promise non-overlap:

void scale(float* restrict dest, const float* restrict src, float factor, size_t n) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; i++) {

dest[i] = src[i] * factor;

}

}Now the compiler knows iterations are independent:

vbroadcastss ymm0, xmm0 ; broadcast factor to all 8 lanes

.loop:

vmovups ymm1, [rsi] ; load 8 floats from src

vmulps ymm1, ymm1, ymm0 ; multiply all 8

vmovups [rdi], ymm1 ; store 8 floats to dest

add rsi, 32

add rdi, 32

sub rcx, 8

jnz .loopEight elements per iteration. For large arrays, this can approach an 8x speedup in some workloads.

In Rust, the equivalent function:

fn scale(dest: &mut [f32], src: &[f32], factor: f32) {

for (d, s) in dest.iter_mut().zip(src.iter()) {

*d = *s * factor;

}

}The signature encodes the non-aliasing constraint. The borrow checker verifies at call sites that dest and src do not overlap. The compiler passes noalias to LLVM, and LLVM generates the same vectorized loop.

In C, restrict is a promise we can break. In Rust, the borrow checker enforces it. The generated code is identical. The safety guarantee is not.

This is why aliasing rules exist. They are the information the optimizer needs to use the hardware effectively. C provides this through type rules and programmer annotations. Rust provides it through static analysis. The CPU does not care which language we used. It cares whether the instructions match the actual memory access patterns.

Part II will explore what happens when objects own resources that must be released: the question of who calls free.